Visa d'Or humanitaire du CICR

2011-2024 Rétrospective

Créé en 2011, le Visa d’Or humanitaire du CICR est un prix de photojournalisme qui récompense une fois par an un·e photojournaliste professionnel·le ayant couvert une problématique humanitaire en lien avec un conflit armé. Ce prix s’intègre dans le festival international de photojournalisme Visa pour l’image.

Doté de 8 000 euros, ce prix répond à un double objectif, à savoir, valoriser le travail que réalisent chaque jour les photojournalistes sur le terrain, mais aussi et avant tout, alerter le plus grand nombre de personnes sur le non-respect du droit international humanitaire.

Au fil de ses 14 éditions, le Visa d’Or humanitaire a exploré diverses facettes des conséquences humanitaires des conflits armés :

● De 2011 à 2014 : Respect de la mission médicale en temps de guerre

● De 2015 à 2017 : Les femmes dans la guerre

● De 2018 à 2021 : Les guerres en ville

● De 2022 à 2023 : Déplacements contraints de populations

● 2024 : Le sort des civils dans les conflits armés

Découvrez ici la rétrospective des lauréats du prix du Visa d’Or humanitaire du CICR.

Attention, les photos contenues dans cette rétrospective peuvent heurter la sensibilité de certaines personnes. Les textes et légendes sont ceux des photojournalistes et n’engagent ou n’expriment pas les positions du CICR.

Created in 2011, the Humanitarian Visa d'Or is a photojournalism prize awarded once a year to a professional photojournalist who has covered a humanitarian issue related to an armed conflict. The prize is part of the Visa pour l'image international photojournalism festival.

The prize, worth 8,000 euros, has a dual objective: to highlight the work that photojournalists do every day in the field, and above all to alert as many people as possible to the non-compliance with international humanitarian law.

In its 14 editions, the Humanitarian Visa d'Or has explored various facets of the humanitarian consequences of armed conflict:

● From 2011 to 2014: Respect for medical missions in wartime

● From 2015 to 2017: Women in war

● From 2018 to 2021: Wars in cities

● 2022 to 2023: Forced displacement of populations

● 2024: The fate of civilians in armed conflicts

Discover the retrospective of the winners of the Humanitarian Visa d'Or award.

Please note that the photos contained in this retrospective may offend the sensibilities of some people. The texts and captions are those of the photojournalists and do not commit or express the positions of the ICRC.

2024

Les déplacés du Nord-Kivu / The displaced of North-Kivu

Hugh Kinsella Cunningham, English below

Dans l’est de la République démocratique du Congo (RDC), dans la province du Nord-Kivu, un conflit armé oppose les forces gouvernementales et le groupe armé M23. Plus de 2,4 million de civils ont été contraints de fuir et de chercher refuge dans de vastes camps de déplacés. Séquelle du génocide rwandais de 1994, le conflit s’est intensifié jusqu’à atteindre un niveau critique. Sur la ligne de front, les forces armées de la RDC tentent de ralentir l’avancée des rebelles. Des forces militaires et des mercenaires de plusieurs pays sont présents sur le terrain, utilisant des armes lourdes et menant des frappes aériennes. Alors que chaque camp cherche à s’emparer de territoires, les roquettes, l’artillerie et les mortiers ont commencé à toucher des cibles civiles, dont des camps de déplacés, faisant de nombreuses victimes.

Pour les civils pris au piège derrière la ligne de front, la communauté internationale est impuissante et aucun signe ne laisse envisager une issue pacifique. De nombreuses familles ont été déplacées à maintes reprises, notamment lors de l’offensive du M23 lancée en 2022.

Au cours des deux années de combat, les lignes de front se sont contractées ; les civils qui fuient vers la sécurité avec tous les biens qu'ils peuvent porter ont été repoussés dans un périmètre de sécurité de plus en plus restreint autour de la ville de Goma. Pourtant, même dans les camps de déplacés surpeuplés, la sécurité n'est pas garantie : les maladies sont omniprésentes, la nourriture rare et les violences sexuelles courantes. La menace de nouvelles violences est réelle ; les opérations militaires se déroulant dans les environs, à portée de voix.

Ce reportage est le fruit d’un travail de couverture de la crise du M23 à temps plein depuis la résurgence du conflit. Les images du contexte humanitaire et du conflit ont été réalisées en 2022, 2023 et 2024, lorsque le conflit s'est intensifié de façon dramatique et que la capitale provinciale de Goma a été progressivement encerclée.

In the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), in the province of North Kivu, armed conflict is raging between government forces and the M23 armed group. More than 2.4 million civilians have been forced to flee and seek refuge in vast camps for the displaced. A sequel to the 1994 Rwandan genocide, the conflict has escalated to a critical level. On the front line, the DRC's armed forces are trying to slow the advance of the rebels. Military forces and mercenaries from several countries are present on the ground, using heavy weapons and carrying out air strikes. As each side seeks to seize territory, rockets, artillery and mortars have begun to hit civilian targets, including camps for displaced persons, causing numerous casualties.

For the civilians trapped behind the front line, the international community is powerless and there is no sign of a peaceful outcome. Many families have been repeatedly displaced, particularly during the M23 offensive launched in 2022.

Over the course of two years of fighting, the front lines have contracted; civilians fleeing to safety with whatever possessions they can carry have been pushed back into an ever-narrowing security perimeter around the city of Goma. Yet even in the overcrowded camps for the displaced, safety is not guaranteed: diseases are rife, food is scarce and sexual violence is commonplace. The threat of further violence is real, with military operations taking place in the surrounding area.

This report is the fruit of full-time coverage of the M23 crisis since the resurgence of the conflict. The images of the humanitarian context and the conflict were taken in 2022, 2023 and 2024, when the conflict intensified dramatically and the provincial capital of Goma was gradually encircled.

Portfolio

Interview

Jury

Christophe Martin

Jean-François Corty

Claude Guibal

Cyril Drouhet

Véronique Gaymard

Isabelle de Lagasnerie

Marie-Hélène Barberis

Recherchiste-documentaliste indépendante

Frédéric Joli

Fondateur du Visa d’Or humanitaire

2023

Le chemin de la dernière chance / Paths of Desperate Hope

Federico Rios Escobar, English below

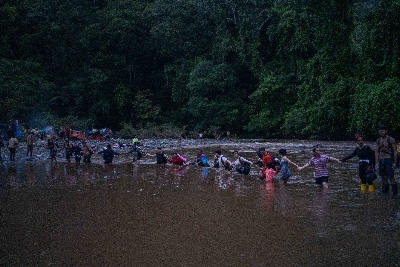

La périlleuse jungle du Daríen, située entre l’Amérique du Sud et l’Amérique centrale, est le point de convergence de deux crises : d’une part, la crise économique et la situation humanitaire catastrophique en Amérique latine, de l’autre, les vives tensions autour de la politique migratoire aux États-Unis.

La région du Darién est une étroite bande de terre entre l’Amérique du Sud et l’Amérique du Nord. Un enchevêtrement montagneux sans aucune route, qui depuis des décennies est considéré comme le chemin de la dernière chance, un parcours parsemé de dangers : des rivières impétueuses, des à-pics vertigineux, des étendues de boue meurtrières et des bandits prêts à kidnapper, à attaquer et à tuer.

En 2022, quelque 250 000 personnes dont au moins 33 000 enfants ont traversé la jungle du Darién. D’ici la fin de l’année 2023, ils devraient être près de 400 000 à avoir fait le voyage, la plupart pour rejoindre les États-Unis.

En 2022, la grande majorité des personnes qui ont franchi la région du Darién étaient des Vénézuéliens, souvent exténués par des années de chaos économique. Mais parmi les migrants qui traversent la jungle, ils sont nombreux aussi à venir de Cuba, d’Haïti, d’Équateur et du Pérou. Et aujourd’hui, il y a également de plus en plus d’Afghans qui fuient les talibans.

Le périple commence dans une petite ville côtière de Colombie. Le parcours traverse ensuite plusieurs fermes et communautés autochtones, franchit la redoutable « colline de la mort », puis longe plusieurs rivières avant d’atteindre un camp géré par les autorités au Panama.

Le gouvernement américain fait tout son possible pour bloquer cette voie. En avril, les États-Unis et leurs alliés dans la région ont annoncé une campagne de soixante jours pour tenter de mettre un terme à ces mouvements illicites de personnes. Le gouvernement américain a également imposé de nouvelles règles qui rendront plus difficile l’entrée aux États-Unis pour tous les demandeurs d’asile, y compris les Afghans.

Aujourd’hui, plus de quatre-vingts nationalités tentent ce voyage périlleux à destination des États-Unis, risquant tout dans l’espoir d’un meilleur avenir pour leur famille.

Two crises converge at the perilous stretch of land between South and Central America known as the Darién Gap. There is the economic crisis and the humanitarian disaster in Latin America, plus the bitter fight over immigration policy in the United States.

The Darién Gap is the sliver of land between South and North America. It is a mountainous tangle with no roads, and for decades has been seen as a last resort, with notorious challenges: rivers that sweep away bodies, hills that cause heart attacks, mud able to swallow up children, and bandits ready to kidnap, attack and kill.

In 2022, some 250,000 people, including at least 33,000 children, traveled through the Darién Gap. By the end of 2023, it is expected that as many as 400,000 will have made the journey, nearly all intent on reaching the United States.

In 2022, the overwhelming majority of people crossing the Darién Gap were Venezuelan, many worn down by years living in a failed economy, but they are just part of a diverse range of migrants walking through the jungle. Others crossing in significant numbers are from Cuba, Haiti, Ecuador and Peru, and there are also Afghans fleeing the Taliban who now form one of the fastest growing groups.

The story begins in a Colombian beach town, passes through several farms and indigenous communities, across the mountain aptly named the Hill of Death, and then along several rivers before reaching a government camp in Panama.

The United States government is trying hard to cut off the route. In April, the U.S. and its allies in the region announced a 60-day campaign intended to end the illicit movement of people through the Darién Gap. The government has also imposed new rules that are expected to make it harder for all asylum seekers, including Afghans, to enter the United States.

Today, more than 80 nationalities attempt the perilous passage on their way to the United States, risking all in the hope of a better future for their families.

Portfolio

Interview

Jury

Halimatou Amadou

Véronique Gaymard

Marie-Hélène Barberis

Recherchiste-documentaliste indépendante

Isabelle de Lagasnerie

Cyril Drouhet

Rony Brauman

Claude Guibal

Abdulmonam Eassa

Lauréat du Visa d'Or humanitaire en 2019

2022

Les routes de la mort / Fatal Crossings

Sameer Al-Doumy, English below

Réalisé entre août 2020 et mai 2022, ce reportage met en lumière la crise migratoire dans le nord de la France.

Après des années de périple, transitant de pays en pays, de nombreux migrants qui ont fui la guerre ou des catastrophes naturelles se retrouvent à Calais. Ils passent alors des semaines dans des camps de fortune sur la côte française, à espérer pouvoir rejoindre leur destination finale, le Royaume-Uni.

Après avoir payé environ 3 000 euros par personne à des passeurs, ils embarquent à bord d’un canot pneumatique équipé d’un tout petit moteur, et tentent de traverser la Manche illégalement pour atteindre l’Angleterre afin de commencer une nouvelle vie.

Le 24 novembre 2021, le naufrage d’un canot gonflable transportant des migrants faisait 27 morts au large de Calais. Ce drame n’a cependant entraîné aucune inflexion des politiques migratoires sécuritaires qui, selon de nombreux observateurs, en sont pourtant la cause.

Entre le début de l’année 2021 et la date de ce naufrage, 31 500 migrants ont traversé la Manche depuis la France pour se rendre au Royaume-Uni. Depuis le Brexit qui a entraîné une sécurisation accrue du port de Calais et de l’Eurotunnel que les migrants empruntaient en se cachant à bord de véhicules, les tentatives de traversée en embarcations légères sont devenues très fréquentes. Mais cette traversée est périlleuse et il est à craindre qu’après la Méditerranée, la Manche ne devienne un nouveau cimetière à ciel ouvert.

The report, covering the period from August 2020 to May 2022, presents the migration crisis as experienced in the north of France.

Many migrants have spent years crossing country after country, fleeing war or natural disaster, then reach the city of Calais on the French side of the strait that is the narrowest part of the English Channel. There they spend weeks in makeshift camps hoping and waiting to reach the United Kingdom, their ultimate destination.

People smugglers charge 3,000 euros for each passenger boarding an inflatable dinghy with a small outboard motor to cross the Channel and land illegally in England in their quest for a new life.

On November 24, 2021, an inflatable dinghy with 27 migrants on board sank off the coast of Calais. These tragedies have no effect on migration policies, yet, according to observers, such policies aimed at border security are the cause of these dramas.

Between January 2021 and November 24 when the tragedy occurred, a total of 31,500 migrants crossed the Channel from France to the United Kingdom. For, since Brexit, with more stringent security checks at the port of Calais and the entrance to the Eurotunnel where migrants hide on board vehicles, more and more have been attempting to cross aboard flimsy dinghies. The crossing is fraught with danger and now, after the Mediterranean, the fear is that the English Channel could become a new maritime cemetery.

Portfolio

Interview

Jury

Véronique Gaymard

Marie-Hélène Barberis

Recherchiste-documentaliste indépendante

Isabelle de Lagasnerie

Cyril Drouhet

David-Pierre Marquet

Luc Hermann

Claude Guibal

Lucas Menget

Florian Seriex

2021

Arméniens, un peuple en danger / Armenians – Endangered People

Antoine Agoudjian, English below

En 1991, après l’effondrement de l’URSS, le Haut-Karabakh, enclavé et peuplé majoritairement d’Arméniens, proclame unilatéralement par référendum son indépendance de l’Azerbaïdjan. Il s’ensuit une guerre de quatre années opposant l’Arménie à l’Azerbaïdjan qui s’achève par une victoire arménienne. En 1994, l’OSCE crée au sein du Groupe de Minsk un cadre approprié à des négociations placées sous les auspices des États-Unis, de la France et de la Russie. L’objectif est d’obtenir des belligérants un accord de cessation des hostilités en vue du déploiement d’une force multinationale de maintien de la paix.

Malgré tout, le 24 septembre 2020, les hostilités reprennent pour une durée de 44 jours. Le 10 novembre, un accord de cessez-le-feu entre en vigueur. L’Azerbaïdjan garde les territoires conquis et récupère à terme la totalité des districts entourant le Haut-Karabakh d’où les forces arméniennes doivent se retirer. De leur côté, les Arméniens conservent un droit de passage au niveau du corridor de Latchin, sous le contrôle des forces de paix russes.

Toute la région demeure pour autant meurtrie par plus d’un siècle de tensions et de conflits successifs aux conséquences humanitaires terribles pour les populations civiles.

After the USSR collapsed in 1991, Nagorno-Karabakh, an area populated mostly by ethnic Armenians, held a referendum and unilaterally declared independence from Azerbaijan. Four years of war followed between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which ended with an Armenian victory. In 1994, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe tasked its Minsk Group, co-chaired by France, Russia and the United States, with facilitating a negotiated resolution to the conflict between the two sides. The objective was to reach an agreement on an end to hostilities and to enable the deployment of a multinational peacekeeping force.

On 24 September 2020, hostilities flared up again, lasting 44 days. On 10 November, a ceasefire agreement came into effect. Azerbaijan kept all conquered territory and recovered all of the districts surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh, which Armenian forces had agreed to evacuate. In exchange, the Armenians maintained the right of safe passage along the Lachin corridor, which was placed under the control of Russian peacekeepers.

Despite this agreement, the entire region remains scarred by more than a century of ethnic tensions and successive conflicts that have caused terrible suffering for civilians.

Portfolio

Interview

Jury

Isabelle de Lagasnerie

Cyril Drouhet

Magdalena Herrera

David-Pierre Marquet

Luc Hermann

Claude Guibal

Lucas Menget

Teresa Plana Casado

2020

Guerrero oublié / Forgotten Guerrero

Alfredo Bosco, English below

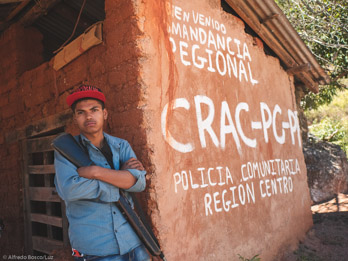

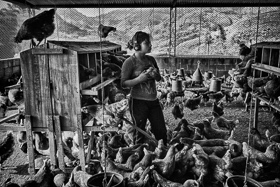

Ce reportage documente la situation sociale et politique actuelle dans l'État mexicain de Guerrero, une région unique dans la guerre liée à la drogue.

Le Guerrero est la principale zone productrice de pavot du pays. Contrairement aux autres États mexicains, souvent contrôlés par une seule organisation, le Guerrero concentre le plus grand nombre de groupes criminels. Pas moins de quarante cartels et groupes de défense autoproclamés, autodefensas, s'affrontent pour le contrôle de la production et du trafic de drogue – l'héroïne destinée au marché américain avant tout – mais aussi d'autres rackets, dont l'extorsion. Dans les grands centres urbains comme Chilpancingo, Chilapa de Alvarez ou encore à Acapulco, ville autrefois touristique, des luttes internes brutales pour le contrôle territorial sèment la terreur parmi les habitants. N'importe qui peut devenir une victime. La violence y est terrible.

L’insécurité règne, obligeant souvent les habitants des plus petites villes à abandonner leurs foyers à la recherche de sécurité. Une des conséquences est l’apparition d’un nombre croissant de pueblos fantasma, villages fantômes.

Au Guerrero, il est facile de mourir, mais il est encore plus facile de disparaître. En 2014, la disparition de 43 étudiants d'Ayotzinapa avait d’ailleurs fait la une des médias internationaux.

Dans ce travail intitulé “Guerrero oublié”, l’ensemble des photographies ont été prises en 2018, 2019 et 2020 dans différentes parties de l'État de Guerrero.

This reportage documents the current social and political situation in the Mexican state of Guerrero, a unique player in the country’s drug war.

Guerrero hosts the largest poppy cultivation in the country but unlike any other state under the control of a single organisation, Guerrero is hostage to more criminal groups than any other region. Forty cartels and self-proclaimed defence groups (autodefensas) fight each other for control over drug production and trafficking - heroin for the U.S. market above everything else - and other rackets including extortion. In larger urban centres such as Chilpancingo, Chilapa de Alvarez and the once famous Acapulco, brutal internal fights spread terror among the locals for territorial control. Anyone can become a victim and the violence is terrible.

The chronic lack of basic security often forces inhabitants of smaller towns to abandon their homes in search for safety. A consequence is the increasing number of pueblos fantasma.

It’s easy to die in Guerrero but even easier to disappear, as the 2014 disappearance of 43 students in Ayotzinapa showed to the international media.

Pictures were taken in 2018, 2019 and 2020 in different parts of the state of Guerrero.

Portfolio

Interview

Jury

Isabelle de Lagasnerie

Luc Mathieu

Cyril Drouhet

Magdalena Herrera

David-Pierre Marquet

Luc Hermann

Benoît Schaeffer

Claude Guibal

2019

La fin (sans espoir ) de l'injustice / Unexpected end of injustice

Abdulmonam Eassa, English below

Une ville assiégée n’est rien d’autre qu’une gigantesque prison, où les civils et leurs proches sont pris au piège.

Seuls les rêves et les souvenirs permettent de s’échapper, l’espace d’un instant fugace. La réalité ressurgit inlassablement pour prendre sa revanche et nous replonger dans un gouffre d’horreurs et de souffrances quotidiennes. Le bruit des tirs d’artillerie et des frappes aériennes et le spectre de la mort envahissent tout, de même que la faim, le froid glacial, la flambée des prix et les pertes sans fin.

Jusqu’à fin mars 2018, les bombes frappaient encore les villes et les villages de la Ghouta orientale, sans répit, semant la peur et la destruction comme jamais depuis le début du siège en 2013.

En l’espace de deux mois à peine, le paysage et tous les points de repère ont totalement changé. Les mosquées, les hôpitaux et les écoles ont été détruits.

Ces frappes étaient une forme de punition collective pour tous ceux qui vivaient sous le siège, et un avertissement adressé aux autres quartiers et villes rebelles. Les civils innocents, empêchés de quitter les abris pour mener leurs activités, étaient piégés et terrorisés par les bombardements incessants. Certains sont morts dans ces abris où ils pensaient être en sécurité.

La petite enclave de la Ghouta orientale, contrôlée par les brigades de l’opposition et quelques factions islamistes, justifiait, aux yeux de Bachar el-Assad, de mobiliser les vastes capacités militaires du régime, avec l’appui aérien des Russes, et d’avoir recours à tout type de munitions, tuant des milliers de civils innocents. Un grand nombre de combattants et de civils ont fini par être évacués de force vers le nord de la Syrie, après un accord injuste en vertu duquel plus de 60 000 habitants ont été contraints de quitter leur maison et leurs terres.

A city under siege is nothing but a huge prison, traps you and your loved ones inside without any possibility of leaving.

The only escape is to take refuge in your dreams and memories, but this is only temporary - every time reality hits you back with its revenge (wrath?), and drags you down the hole of everyday horrors and suffering. Sounds of shelling, airstrikes, the threat of death that follows you everywhere you go, starvation, freezing weather, skyrocketing prices and endless losses.

Up until a late moment in March 2018, airstrikes were hitting the villages of Eastern Ghouta on a daily basis, a terrorizing and destructive rate that has not been seen throughout the years of the siege - since 2013.

In under 60 days, the landmarks of the cities and villages changed completely with the destruction in mosques, hospitals and schools.

The shelling was a form of collective punishment to everyone living inside the siege, and as a lesson to other rebellious neighborhoods and cities. During this period, innocent people could not leave the shelters to secure their daily needs because of their deep fear from the constant shelling. Some died in shelters trying to protect themselves.

The small pocket of eastern Ghouta controlled by opposition brigades and certain Islamist factions was, for the Syrian regime, sufficient justification for mobilizing its vast military capabilities, backed in the air by the Russians, and using all kinds of munitions, killing thousands of innocent civilians. Finally, large numbers of fighters and civilians were forcefully evacuated to northern Syria, after an unfair deal that displaced more than 60,000 residents from their homes and land.

Portfolio

Interview

Jury

Isabelle de Lagasnerie

Lucas Menget

Cyril Drouhet

Jérome Huffer

Magdalena Herrera

David-Pierre Marquet

Alyona Synenko

Benoît Schaeffer

Claude Guibal

2018

Des héroïnes fabriquées par la guerre

Véronique de Viguerie, English below

Depuis 2006, le Yémen est l’un des pires endroits où vivre pour une femme.

La guerre civile qui oppose depuis trois ans les rebelles houthis au gouvernement en exil, soutenu par une coalition armée emmenée par l’Arabie saoudite, n’a fait qu’empirer les choses. Pourtant, malgré l’omniprésence de la mort et les privations qu’inflige cette guerre, les femmes assument des rôles sociétaux auparavant dominés par les hommes. De par leur absence, parce qu’enrôlés, blessés ou tués, les femmes deviennent cheffes de famille, prodiguent des soins, s’inscrivent à l’école, organisent le commerce et assument aussi des rôles politiques et d’activistes.

Amat, premier ministre du gouvernement dit “des enfants”, jeune fille de 17 ans, est l’une des 33 ministres, pour la plupart des garçons. Elle lutte contre la corruption et persuade les commandants en première ligne de libérer des enfants soldats ou d’empêcher les mariages d’enfants. Dans les hôpitaux publics comme celui de Saada, un bastion houthi, les victimes des bombes à sous-munitions ou de la famine arrivent chaque jour. La majeure partie du personnel est composée de femmes suffisamment motivées pour venir travailler sans percevoir de salaire depuis plus d’un an.

Dans l’enseignement supérieur, les femmes sont aujourd’hui plus nombreuses que les hommes dans les domaines de l’informatique, des sciences et du droit. Elles veulent plus tard jouer un rôle très actif dans la société yéménite.

Après une année de tentatives pour entrer dans le pays, j’ai finalement réussi à passer un mois, d’octobre à novembre 2017, dans le nord du Yémen.

Since 2006, Yemen is one of the worst country to live as a woman. The three-year civil war, between rebel Houthis, the exiled government, and a Saudi-backed coalition, has only made things worse. And yet, amid the death and deprivation of this war, women are assuming societal roles that were previously dominated by men. As more men are conscripted, wounded or killed, more women are the sole providers for their families; practicing medicine; enrolled in school; selling goods; and assuming political and activist roles.

Ahmat, Prime minister of the so called children government, a strong-willed 17-year-old, one of 33 ministers – mostly boys – is working to fight corruption and to persuade commanders on the frontlines to release child soldiers or to prevent child marriages. In public hospitals like the one in Saada, a Houthi stronghold, victims of cluster bombs and famine arrive daily. Most of the remaining staff is female, committed enough to come to work despite not having received their salaries for more than a year. In higher education, where people have access to it, female graduates outnumber males in IT, sciences and law schools. The young women in these schools want to be active in Yemeni society.

Amid the tragedy of Yemen’s long war and the loss of men, women are being forced into new roles. Women are not passive spectators in the conflict unfolding in Yemen.

After a year trying to get into the country, I finally spent a month in North Yemen in October and November 2017.

Portfolio

Interview

Jury

Isabelle de Lagasnerie

Albéric de Gouville

Lucas Menget

Cyril Drouhet

Magali Corouge

Jérome Huffer

Magdalena Herrera

Kathryn Cook Pellegrin

David-Pierre Marquet

2017

Ayacucho

Angela Ponce Romero, English below

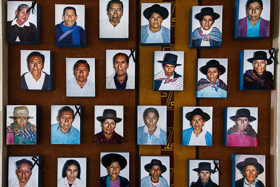

Ayacucho, du quechua aya signifiant « cadavre » et cucho signifiant « coin », peut se traduire par le « coin des morts ».

Les années 1980 et 1990 marquent l’une des périodes les plus tragiques pour la ville d’Ayacucho et l’histoire du Pérou. Le conflit armé déclenché par le Parti communiste péruvien (plus connu sous le nom de Sentier Lumineux ou Sendero Luminoso) et la réponse armée du gouvernement ont entraîné la mort et la disparition de dizaines de milliers de personnes à Uchu, Accomarca, Lucanamarca et Cayara.

Les femmes de ces villages ont été victimes d’assassinats indiscriminés, de terreur et de soumission. Les filles et les jeunes femmes ont été enrôlées dans différents groupes subversifs ; elles ont été mariées de force, utilisées comme sentinelles et victimes d’abus sexuels. Aujourd’hui, les femmes, les veuves et les orphelins qui ont survécu continuent d’exiger justice et vérité.

Ce sujet couvre les cérémonies de commémoration organisées à Ayacucho, au Pérou, en 2016 et 2017, afin de créer une mémoire collective et éviter que de telles atrocités ne se reproduisent.

"Ayacucho, from the Quechua words aya meaning “corpse” and cucho meaning “corner,” is the “corner of the dead.”

The last two decades of the twentieth century saw one of the most tragic times for the city of Ayacucho and the history of Peru. The armed conflict initiated by the Communist Party of Peru (more commonly known as the Shining Path, Sendero Luminoso) and the response by the government led to tens of thousands of people dying and disappearing in Uchu, Accomarca, Lucanamarca and Cayara.

Women in the communities were victims of indiscriminate killings and subjected to a regime of terror and submission. Girls and young women were recruited to work for subversive groups; they were forced into unwanted marriages, used as security guards, and were victims of sexual abuse. Today, the surviving women, widows and orphans continue to seek justice and truth.

This photo-essay covers commemorative events held in Ayacucho, Peru, in 2016 and 2017, to create a collective memory, and to stop such a period of violence from ever happening again.

Portfolio

Interview

Jury

Armelle Canitrot

Cyril Drouhet

Magali Corouge

Romain Lacroix

Magdalena Herrera

Sébastien Carliez

David-Pierre Marquet

2016

Nés dans le conflit : les enfants soldats en Colombie / Born into Conflict: Child soldiers in Colombia

Juan Arredondo, English below

"Ces deux dernières années, j'ai photographié et interviewé dans toute la Colombie des enfants soldats "toujours d'active" mais aussi d'autres démobilisés. J'ai découvert le silence profond entourant quelque 6000 jeunes hommes et femmes enrôlés dans des groupes armés et dont la vie a été dévastée.

On estime que 25 à 50 % de ces combattants sont des femmes, parfois des gamines à peine âgées de neuf ans. Les filles reçoivent la même formation que les garçons, elles ont appris à manier les armes, à recueillir des renseignements et participent à des opérations militaires; mais elles sont aussi victimes d'abus sexuels, souvent à la merci de leurs commandants et, dans la plupart des cas, forcés d'avorter si elles tombent enceintes.

Ces survivantes sont aujourd'hui confrontées à la difficulté de retourner dans leurs familles vivant souvent dans l'extrême pauvreté. En outre, elles sont stigmatisées par la société colombienne, qui les considère comme des criminelles. Face à l'instabilité économique, la discrimination, le manque d'éducation et le peu de soutien familial, la plupart de ces enfants sont contraints de renouer avec la violence à travers des activités criminelles".

"For the past two years I've been photographing and interviewing current and former child soldiers throughout Colombia. What I have come across is a silenced latent crisis that has devastated the lives of the estimated 6,000 young men and women currently enlisted in illegal armed groups.

It is estimated that a quarter to nearly half of recruited combatants are women including girls as young as nine years old. Girls receive the same training as their male counterparts, they are taught to handle weapons, collect intelligence and take part in military operations; but they are also victims of sexual abuse at the hands of their commanders and in most instances forced to have an abortion if they get pregnant as a result of this abuse.

These young survivors are faced with the hardship of returning to their families living in extreme poverty, communities that shun them – or both. Moreover, they are stigmatized by the collective fear of Colombian society at large, which views them as criminals, and hence face economic instability because of discrimination, lack of education and insufficient family support. As a result, most of these children are forced to enter a cycle of violence and criminality that perpetuates this social conflict."

Portfolio

Interview

Jury

Nick Danziger

Photographe. Il a passé près de 25 ans à photographier le monde des défavorisés et des dépossédés.

Photographer. He has spent much of the last 25 years photographing the world most dispossessed and disadvantaged.

Daphné Anglés

Armelle Canitrot

Jérome Huffer

Magali Corouge

David-Pierre Marquet

2015

Le procès de Minova / Minova rape trials

Diana Z. Alhindawi, English below

Entre le 12 et le 19 février 2014, un tribunal temporaire a été installé à Minova, une localité au bord du lac Kivu dans l’est de la République démocratique du Congo. Les procès se tiennent habituellement à Goma, mais pour les victimes des viols commis à Minova, le voyage jusqu’à Goma aurait été trop onéreux. C’est donc le tribunal qui s’est déplacé pour entendre leurs témoignages.

39 membres des Forces armées de la RDC (FARDC) ont été accusés d’actes de violence commis pendant dix jours de terreur en novembre 2012, durant lesquels plus de 1 000 femmes, hommes et enfants auraient été violés dans la seule ville de Minova. En définitive, 37 militaires ont été inculpés pour viols. L’attaque contre les civils a eu lieu alors que les soldats des FARDC fuyaient les rebelles du Mouvement du 23 mars qui s’étaient emparés de la ville stratégique de Goma.

En 2011, la représentante spéciale de l’ONU chargée de la question des violences sexuelles commises en période de conflit a qualifié la République démocratique du Congo de « capitale mondiale du viol ». Le procès de Minova représente une réelle avancée pour la défense des victimes de viol : c’est notamment la première fois qu’autant de soldats sont mis en accusation. Les plaintes ont été entendues par un tribunal militaire et il n’y a aucune procédure d’appel possible auprès d’une autre instance.

En raison de la stigmatisation à l’encontre des victimes de viol, celles qui ont comparu s’étaient habillées de façon à conserver l’anonymat ; mais même avec ces précautions, seulement 47 femmes sont venues témoigner.

La cour a rendu son verdict le 5 mai 2014 : seuls deux soldats ont été reconnus coupables de viols. L’un d’eux a été condamné à une peine de réclusion à perpétuité.

Between February 12 and 19, 2014, a temporary courtroom was set up in Minova, a market town on the shore of Lake Kivu in eastern DR Congo. Trials are usually held in Goma, but for the rape victims living in Minova, the trip to Goma would have been prohibitively expensive, so the court came to them, to hear their testimony.

Thirty-nine members of the DRC Armed Forces (FARDC) were on trial on charges relating to violence committed in a ten-day rampage in November 2012 when, according to estimates, more than 1,000 women, children and men were raped in the town of Minova alone. In the end, 37 members of the military faced rape charges. The civilians were attacked when FARDC troops were fleeing rebels from the March 23 Movement that had captured the strategic city of Goma.

In 2011, a UN special representative on sexual violence in conflict described the Democratic Republic of Congo as the “rape capital of the world.” The Minova trials stand as a great step forward in justice for rape victims, particularly given the unprecedented situation with such a large number of members of the armed forces accused. The cases were heard by a military tribunal, and there is no recourse to any court of appeal.

For victims, there is great stigma associated with rape, so those who appeared in court were swathed in garments to conceal their identity, and even then only 47 women came forth to testify.

When the verdicts were handed down on May 5, 2014, two of the 37 members of the armed forces accused of rape were convicted. One of the two was given a life sentence.

Portfolio

Interview

Jury

Georges Comninos

Chef de la délégation du CICR en France. En trente ans de carrière humanitaire, il a travaillé en Afrique, au Proche et Moyen-Orient et en Amérique Latine.

Head of ICRC Delegation in France. He has been working for the ICRC since 30 years, in the Near and Middle East, Africa and Latin America.

Daphné Anglés

Armelle Canitrot

Cyril Drouhet

Magdalena Herrera

Jérôme Huffer

David-Pierre Marquet

2014

Crise humanitaire en Centrafrique / Humanitarian Crisis in the Central African Republic

William Daniels, English below

La République centrafricaine est plongée dans une crise humanitaire sans précédent. Après un an de terreur imposée par la Séléka - une rébellion majoritairement musulmane -, ce sont désormais les milices chrétiennes anti-balaka qui, par vengeance démesurée, tuent et chassent tous les musulmans de l’ouest du pays. Des quartiers entiers sont assiégés, des femmes et des enfants sont attaqués à la grenade. Face au manque de soutien international, les forces africaines de la MISCA (Mission internationale de soutien à la Centrafrique sous conduite africaine) et l’armée française peinent à contenir les massacres et les déplacements de population. Le pays compte près d’un million de déplacés, soit un quart de sa population, qui n’ont pas ou peu accès à la nourriture et aux soins.

La Centrafrique a longtemps été considérée comme une crise oubliée en raison du manque d’investissement de la communauté internationale. Cela fait 40 ans que la République centrafricaine est en état de vulnérabilité chronique. Selon l’OMS, l’espérance de vie -la deuxième plus faible au monde - est de 48 ans. Le système de santé, quasi inexistant, repose en grande partie sur l’engagement d’ONG internationales. Le taux de malnutrition était de 38 % avant la crise actuelle. Le paludisme y est holoendémique : chaque habitant du pays est infecté au moins une fois par an.

Depuis décembre 2013, je me suis rendu plusieurs fois en Centrafrique. J’ai couvert la catastrophe humanitaire dans les camps de déplacés de la capitale, comme l’impressionnant camp de l’aéroport M’Poko qui, en quelques jours, s’est vu grossir de 100 000 personnes en grande majorité chrétiennes ou animistes, qui fuyaient les combats entre Séléka et anti-balaka.

Je me suis aussi rendu de nombreuses fois dans les enclaves musulmanes de PK-5, Bégoua, et Boda. Dans chacune le scénario est similaire, les habitants et ceux y ayant trouvé refuge sont assiégés. Quiconque tente d’en sortir risque d’être abattu, parfois même égorgé, démembré. Les anti-balaka qui entourent les enclaves jettent à l’aveugle des grenades qui atteignent au hasard des femmes ou des enfants. La situation sanitaire y est déplorable. L’accès aux soins est très limité. À Boda, la situation était encore plus critique lors de ma visite en avril dernier. La nourriture était difficilement acheminée pour les quelque 10 000 habitants de l’enclave, souvent bloquée par les opérations de harcèlement des anti-balaka sur la route de Bangui. De nombreux enfants souffraient de malnutrition sévère, principalement ceux de l’ethnie peule, discriminée au sein même de l’enclave. Les soins étaient assurés par deux infirmiers et un médecin à mi-temps complètement débordés. Sous la pression de l’armée française, l’hôpital de la ville venait tout juste de rouvrir mais, étant situé à l’extérieur de l’enclave, il était bien trop dangereux pour les musulmans de s’y rendre.

The Central African Republic has been plunged into an unprecedented humanitarian crisis. After a year of terror led by the mainly Muslim rebel Seleka group, anti-Balaka militia wreaked revenge on the Muslims in the west of the country who fled or were killed. Entire districts were under siege; even women and children were victims of grenade attacks. There was little response from the international community. Soldiers with the African-led International Support Mission in the Central African Republic (MISCA) and French troops struggled to stop the massacres and population movements. Nearly one million (one fourth of the population) fled, becoming displaced persons, needing food and medical care.

For a long time the crisis in the Central African Republic was almost forgotten, having triggered little interest or support from the international community. The Central African Republic has been unstable and vulnerable for forty years now. According to the World Health Organization, life expectancy is the second lowest in the world, at only 48 years. The country has no proper healthcare system and relies on the commitment of international NGOs to provide medical care. Before the current crisis, the rate of malnutrition was 38%. Everyone in the country today suffers from malaria, with at least one attack a year.

I have made a number of trips to the Central African Republic since December 2013, and have covered the humanitarian disaster, seeing camps for displaced persons in the capital city, such as M’Poko, a staggering sight at the airport where in the space of just a few days there was an influx of 100 000 people, mostly Christians and animists, fleeing the fighting between Seleka and anti-Balaka forces.

On a number of occasions I have traveled to the remaining Muslim communities, now isolated enclaves at PK-5, Begoua and Boda. Each site had similar scenes, with residents and others who had found shelter there ending up under siege, afraid to leave for fear of being killed, by gunshot, their throat cut, or being dismembered. Anti-Balaka fighters around the enclave throw grenades randomly, hitting women and children. Hygiene and health are appalling, and there is only minimal access to medical care.

When I returned to Boda in April this year, the situation was even more critical. It was difficult to get food supplies to the 10 000 people living isolated in the enclave there, as anti-Balaka harassment tactics often block the road to Bangui. Many children are suffering from severe malnutrition, mainly Peul children as the Peul ethnic group is subjected to discrimination within the enclave. Some medical care was provided by a part-time doctor and two nurses, but they are overwhelmed by the demand. The local hospital responded to pressure from the French forces, and recently opened again, but as it is outside the enclave, it was still too dangerous for Muslims to go there.

Portfolio

Interview

Jury

Didier François

Est depuis 2007, grand reporter à Europe 1. Il était précédemment journaliste à Libération. Durant ses 30 ans de carrière, il a couvert de nombreux conflits armés.

French reporter working for French radio Europe 1 since 2007. He previously worked for the daily newspaper Libération. In his 30 year-career, he has covered many armed conflicts.

Magdalena Herrera

Daphné Anglés

Jérôme Huffer

Caty Forget

Pierre Gentile

Georges Comninos

2013

La vie et la mort à Alep / Life and Death in Aleppo

Sebastiano Tomada, English below

Depuis juillet 2012, la bataille fait rage entre les forces gouvernementales et les insurgés de l’Armée syrienne libre (ASL) qui se battent pour le contrôle d’Alep, la grande ville du nord. Les centres médicaux accueillant les blessés dans les quartiers tenus par les rebelles sont devenus des cibles militaires, ce qui oblige les médecins à travailler dans un réseau clandestin de cliniques et d’hôpitaux. C’est le cas de l’hôpital Dar al-Shifa, naguère une clinique privée appartenant à un homme d’affaires resté loyal au président Bachar el Assad, aujourd’hui transformée en hôpital de campagne où travaillent bénévolement médecins, infirmières et aides-soignants unis par leur opposition au régime, et par la nécessité de soigner les civils autant que les rebelles.

Sebastiano Tomada a commencé par couvrir la révolution syrienne à Idleb, puis tout au long de la frontière avec le Liban, avant de se concentrer sur Alep, où il a pu suivre les avancées et les reculs successifs de l’Armée syrienne libre. Il témoigne de la vie quotidienne et des conditions de soins dans une ville assiégée, nous montrant la cruelle réalité que vivent les hommes, les femmes et les enfants ainsi pris au piège.

Since July 2012, the battle had been raging between government forces and insurgents with the Free Syrian Army (FSA) fighting for control of the northern Syrian city of Aleppo. Medical centers treating casualties in rebel-held districts became a military target, forcing doctors to work in an undercover network of clinics and hospitals. One of these is Dar al-Shifa hospital: previously a private clinic owned by a businessman loyal to President Bashar Assad, Dar al-Shifa became a field hospital run by volunteer doctors, nurses and aides united in their opposition to the regime and the need to provide medical care to both civilians and rebels.

Sebastiano Tomada first covered the Syrian revolution in Idlib and along the border between Syria and Lebanon, then shifted his attention inside Aleppo where he began covering the advances and losses of the Free Syrian Army. With a focus on daily life and medical conditions in a city under siege, Sebastiano shows what is cruel reality for the men, women and children who continue to live in the besieged city of Aleppo.

Portfolio

Interview

Jury

Rony Brauman

Médecin, chercheur, ancien président de Médecins sans Frontières. Il est l’un des fondateurs du Centre de Réflexion sur l'Action et les Savoirs Humanitaires (CRASH).

Physician, researcher, former president of Doctors Without Borders. He is one of the founders of the "Centre de Réflexion sur l'Action et les Savoirs Humanitaires (CRASH)".

Daphné Anglés

Magdalena Herrera

Cyril Drouhet

Jérôme Huffer

Olga Miltcheva

Caty Forget

2012

Syrie, dans Homs / Syria, inside Homs

Mani, English below

À la veille du soulèvement syrien, les adversaires les plus résolus du régime de Bachar el-Assad étaient les premiers à redouter une révolution. Tous gardaient en effet en tête l’écrasement de Hama en 1982, épilogue sanglant d’une insurrection islamiste de trois ans. Le régime syrien, dirigé à l’époque par Hafez el-Assad, le père de l’actuel président, n’avait alors pas hésité à faire tirer à l’arme lourde sur la quatrième ville du pays, au prix de milliers de morts, même si jamais aucun bilan officiel n’a été publié (entre 10 000 et 20 000 morts selon les estimations).

Ces opposants voyaient juste. Depuis le 17 mars 2011 et les premières tueries à Deraa, dans le sud du pays, le pouvoir syrien a privilégié à nouveau la réponse militaire, augmentée à la marge de réformes jugées purement cosmétiques. Confronté à des marées humaines prenant pacifiquement le contrôle des rues et face auxquelles il était désarmé, le régime a tenté de pousser une partie de cette opposition vers la lutte armée, un terrain sur lequel il pensait être à son avantage.

Cette pression a été à l’origine de la constitution de l’Armée syrienne libre, formée de déserteurs et de civils, sans pour autant que les cortèges de la colère, chaque vendredi, ne disparaissent. Mais le calcul de Bachar el-Assad s’est avéré à courte vue puisque c’est une guérilla classique qui s’est mise en place, aussi prompte à céder le terrain lorsque la pression des forces concentrées ponctuellement par le régime est trop forte, qu’elle est rapide à y revenir après le départ des blindés en direction d’un autre bastion rebelle.

L’autre échec du régime tient à son incapacité à restaurer « le mur de la peur » constitué par au moins trois décennies de répression, du massacre de la prison de Tadmor, en 1980, à celui de celle de Sednaya, en 2008. Depuis le début du soulèvement, le régime a pourtant laissé ses milices, les chabiha, se charger de la sale besogne : exécutions sommaires, tortures, nettoyages communautaro-ethniques, viols…

De fait, le pays est livré depuis plus de quinze mois à une violence inouïe. Une violence d’État qui n’a que faire des principes humanitaires les plus fondamentaux. C’est ainsi que les hôpitaux, les services de santé, les médecins ont été la cible des chasses à l’opposant organisées dans tout le pays. Les témoignages recueillis à Homs par les envoyés spéciaux du Monde, le rapport rédigé par l’organisation non gouvernementale Médecins sans frontières font état de véritables battues dans les établissements publics, ne laissant aux blessés d’autre choix que de s’en remettre à des dispensaires de fortune où les médicaments n’arrivent qu’au compte-goutte, lorsqu’ils arrivent.

Pour préserver ses chances de survie, le régime syrien a fait le choix d’une barbarie sans retour qui diffuse la haine et qui nourrit représailles et règlements de comptes. Le choix de la terre brûlée.

Shortly before the Syrian uprising, the first people to sense that revolution was on the way were the most determined opponents of Bashar el-Assad’s régime. They could still remember 1982 and the Hama massacre, the cruel epilogue to crush an Islamist revolt that had been going on for three years. At the time, the régime was led by Hafez el-Assad, the father of the current president, who had no qualms about firing heavy weapons on the fourth largest city in the country, leaving thousands dead, although no official figures were ever released. (According to estimates, the number of dead was between 10 000 and 20 000.)

The opponents were right. Since March 17, 2011, and the first killings in Deraa in the south of the country, the Syrian regime has again opted for a military response, plus a few purely cosmetic reforms on the side. When massive crowds gained control of the streets, peacefully, the régime was faced with a challenge, and attempted to push part of the opposition movement into armed confrontation, an area where it believed it held the advantage.

Under this pressure, the Free Syrian Army formed, their ranks filled with deserters and civilians, and the angry demonstrations still continued every Friday. Bashar el-Assad’s calculation turned out to be short-sighted, as a classical guerilla force took shape, prepared to concede terrain when concentrated forces sent in by the regime from time to time proved to be too powerful, and then quick to return once the armored vehicles had set off for another rebel stronghold.

Another weak point of the regime was that it failed to rebuild the “wall of fear” which had been established over three decades or more of repression – from the Tadmor prison massacre in 1980 to the Sednaya prison massacre in 2008 – and despite the fact that since the beginning of the uprising the régime had set its militia forces, the Shabiha, to do the dirty work: summary executions, torture, ethnic cleansing, attacks on communities, rape and more.

Over the last fifteen months the country has been in the grips of unbelievable violence – the violence of a State with total disregard for even the most basic humanitarian principles. Hospitals, medical centers and doctors have been targeted, as opponents are methodically hunted down across the country. Eye-witness reports from Homs from special correspondents for the newspaper Le Monde and the NGO Médecins sans frontières describe organized hunts through public buildings, and the wounded have no other choice than to rely on makeshift medical centers with little or no medical supplies.

To help maintain its chance of survival, the Syrian regime has chosen the inhumane option, with no going back, spreading hate and triggering reprisals, settling old scores: the choice of the scorched earth policy.

Portfolio

Interview

Jury

Pierre Micheletti

Médecin, universitaire et écrivain. Il fût notamment président de l'ONG française Médecins du Monde. Il est actuellement enseignant à Sciences Po Grenoble.

Physician, academic and writer. He was also President of the French NGO, Doctors fo the World. He currently teaches at Sciences Po Grenoble.

Daphné Anglés

Armelle Canitrot

Cyril Drouhet

Jérôme Huffer

Paul-Henri Arni

Catherine Boniface

2011

"Premier km2 de liberté" : place du Changement, Sanaa, Yémen

The First Square Kilometer of Freedom: Change Square, Sana’a, Yemen

Catalina Martin-Chico, English below

"Martyr, ton sang n’a pas coulé en vain", chantent les révolutionnaires yéménites

Étudiants, chômeurs, laissés-pour-compte et déçus, ils sont tous là, en rangs serrés, sur le parvis de la nouvelle université de Sanaa, rebaptisé « place du Changement ». Ils n’en bougeront pas avant que le président Ali Abdallah Saleh, à la tête du Yémen depuis 33 ans, n’ait quitté le pouvoir. Des reliefs du nord aux vallées du sud, des côtes de la mer Rouge aux wadis de l’Hadramaout, plus une province du Yémen n’échappe désormais aux mobilisations de la jeunesse. Les « révolutionnaires » forment l’un des groupes les plus improbables qui soit. Le premier succès de la révolution est sans doute là. Les Yéménites s’observent et se parlent. Ils se découvrent. Les hommes des tribus échangent avec de jeunes étudiants en communication, des parlementaires socialistes débattent avec des musulmanes, des commerçants de la vielle ville écoutent des officiers des forces aériennes. Peu importe l’uniforme ou le titre. « Nous sommes tous les fils du Yémen ! », aiment à répéter les manifestants.

Au fur et à mesure que le camp du changement s’élargissait, le parti présidentiel connaissait une érosion spectaculaire. Diplomates, ministres, députés, gouverneurs, officiers, cheiks… Ils sont nombreux, ces fidèles partisans d’Ali Abdallah Saleh, à s’être ralliés au mot d’ordre principal des manifestants : le président doit partir et le régime doit tomber. Place du Changement à Sanaa, ou place de la Liberté à Taez, ces milliers de citoyens ont fait le choix d’une méthode de lutte : le pacifisme. La voici, l’autre originalité de cette « révolution » : elle se fait sans armes. Dans un pays où circulent plus de cinquante millions d’armes à feu, et malgré les nombreux contrôles militaires qui filtrent les accès à la capitale, il n’est pas très compliqué de se procurer un AK-47 ou un lance-roquettes. Mais les opposants ont découvert qu’il était possible de revendiquer sans violence, simplement par des mots et une présence. La confrontation armée entre le président Saleh et le clan de la tribu Al-Ahmar, dans le nord de la capitale, a pourtant menacé de faire glisser la « révolution » vers une guerre civile. Les manifestants ont aussi essuyé les tirs aveugles de snipers embusqués sur les toits, les gaz lacrymogènes et les coups de matraque assénés par les forces de la sécurité centrale. Mais, pacifiques jusqu’au bout, eux n’ont pas tiré une seule balle. Alors que le président Saleh est toujours hospitalisé en Arabie Saoudite, les « révolutionnaires » tentent de provoquer un transfert progressif, et pacifique, du pouvoir. Ils réclament aussi la consolidation d’un régime parlementaire. Ce nouveau Yémen qu’ils appellent de leurs vœux devra s’attaquer à la corruption et à l’injustice. Le temps de consacrer un succès qu’ils estiment inéluctable, ils repartiront dans les rues. Ils savent pourtant que les services de sécurité les y attendent. Alors ils chanteront : « Martyr, ton sang n’a pas coulé en vain. »

"Martyr, your blood has not been shed in vain", Chant of the revolutionaries in Yemen

Students, drop-outs, people unemployed or simply disillusioned – they are all there together, packed onto the square outside the new University of Sana’a, and now known as Change Square. They are determined to stay there until President Ali Abdallah Saleh, who has held power in Yemen for 33 years, steps down. From the mountains in the North to valleys in south, from the shores of the Red Sea to the wadis of Hadhramaut, youth movements have reached every province in the country. The “revolutionaries” are an improbable, motley lot, and that is no doubt the first success story for the revolution. The people of Yemen have been looking at one another and speaking to one another; they have been discovering one another. Tribal men have had discussions with young students specializing in communication; socialist parliamentarians have been debating with Muslim women; shopkeepers from the old city have been listening to air force officers. Uniforms and titles are irrelevant: “We are all children of Yemen” proclaim the demonstrators.

As more and more people join the advocates of change, the President’s party has suffered spectacular decline. Diplomats, ministers, parliamentarians, governors, officers and sheikhs, once loyal supporters of Ali Abdallah Saleh, have rallied to the demonstrator’s cause, adopting their call for the president to go and the régime to fall. Change Square in Sana’a and Freedom Square in Taez are focal points for thousands of citizens who have chosen to embrace peaceful resistance. Yes, that is another original feature of the “revolution” – it is being conducted without weapons. In a country with more than 50 million firearms, and despite the many military checkpoints monitoring movements into and out of the city, it is not very difficult to get a Kalashnikov or a rocket-launcher. But opponents to the regime discovered that they could make demands without violence, simply by using words and by being there, although the armed conflict between President Saleh and the Al-Ahmar clan north of the capital almost pushed the “revolution” into a state of civil war. Demonstrators have been targets for snipers on rooftops and teargas and attacks by central security men wielding truncheons. Yet they have remained peaceful pacifists to the end, without firing a single shot. While the president is still in hospital in Saudi Arabia, they have endeavored to bring about a gradual, peaceful shift in power. They have called for a proper and sound parliamentary regime, a new Yemen which they wish to see tackle corruption and injustice. Time is needed to succeed, and for them success is the only possible outcome. In the meantime, they shall return to the streets, quite aware that the security forces are waiting for them there. So they shall chant: Martyr, your blood has not been shed in vain.

Portfolio

Interview

Jury

Jean-Christophe Rufin

Médecin, écrivain, diplomate, membre de l’Académie française, il fût notamment l'un des fondateurs de Médecins Sans Frontières et président d'Action contre la Faim.

Physician, writer, diplomat, member of the Académie Française. He also one of the founders of Doctors Without Borders and President of Action against Hunger.

Daphné Anglés

Armelle Canitrot

Magdalena Herrera

Jérôme Huffer

Thomas Vanden Driessche

Caty Forget